Book Review

In my review last month of Memorandum by Woody Aragon, I wrote about the influence of the Spanish School of magic over the past quarter century or more. Magicians are well aware of the work of Juan Tamariz and his many acolytes when it comes to card magic, but the fact is that there is great innovation occurring in the world of Spanish magic when it comes to coin magic and general close-up magic as well. But publication of card magic always vastly outstrips that of other forms, and what’s more, the books published in Spanish rarely see English translation. Miguel Ángel Gea’s lecture notes and book have not been translated, for example, but this marvelous Spanish coin worker has at least been featured in a 4-DVD set entitled Essence, that any practitioner who is serious about coin magic should investigate.

As it happens, when I first met Miguel in Spain at the Neuromagic 2011 conference, I also met two of his highly regarded Spanish conjuring colleagues, Kiko Pastur and Luis Piedrahita. After the conference I also had the chance to spend a day in Madrid with Luis, exploring food and magic, and I subsequently lectured at a conference of the Close-up Magicians of Galacia during the same trip, a substantial gathering of Spanish close-up magicians.

These names require no introductions for Spanish magi, but if you’re not familiar with Luis Piedrahita, allow me to introduce you. Piedrahita is a star performer in Spain, but interestingly, he reached celebrity standing before the public ever became aware of his conjuring abilities. Among other things, Piedrahita is renowned as a standup comedy performer, who for years has been routinely selling out theaters for his two-hour or longer comedy concerts. He’s also a successful writer for film and television, and the author of half a dozen humor books for the public as well as a children’s book.

While he has been interested in magic since childhood, and won two magic contests in his early 20s, he essentially concealed his magic from the public as his star rose in the worlds of comedy and television. But in 2006 he collaborated with magician Jorge Blass and Rodrigo Sopeña on a magic television series, Nada x aquí, which ran for three seasons and a total of 48 episodes, and for which Piedrahita served collaboratively as a writer, director, and performer. Then in 2011, he was a regular guest for a season of the popular talk show, El Hormiguero, where he would appear each week performing close-up magic for A-list celebrities like Miley Cirus, Jennifer Lawrence, Justin Timberlake and more. (Many of these segments can be found on YouTube, and several are posted below following this review.)

Spending time with Luis, I quickly became aware of his intelligence, passion, knowledge of magic, and what I can only describe as a deeply artistic spirit. He is very much a product of the influence of Tamariz and the Spanish School, but also, like Juan, he has tremendous experience as both a stage and television performer. It’s worth reporting here on Piedrahita’s extensive resumé, because it points to why a close consideration of his work is a worthy effort. It’s interesting and instructive to examine what conclusions he has come to, and what choices he makes as a presenter of close-up magic in general, and coin magic in particular. This is a polished, self-demanding sleight-of-hand performer, who thinks deeply about method and construction, creates thoughtful original presentations, utilizes extremely sophisticated sleight-of-hand technique, and manages to achieve great impact with his work in the most demanding of conditions. I daresay that as far as performers of intimate magic are concerned, I doubt we have ever seen his equivalent on American television on such an ongoing basis, as and his work contains invaluable lessons for any attentive student.

Coins and Other Fables was first published in Spanish in 2011, and was well received by those who could obtain and understand it. Now, published by Conjuring Arts and translated by New York magician Noah Levine (whose Magic After Hours show I’ve written about previously), the English speaking magic world at last has access to this remarkable collection of coin magic. The book describes ten routines, developed and utilized over a ten-year period, that, as the author observes, he has performed “in theaters, on television, in bullrings, corporate events, hot tubs, mountain shelters, and monasteries.”

The book begins with three short essays, one by the author and one each by colleagues Juan Herrera and Manuel Cuesta. Herrara’s entry opens this section with “Beautiful Little Empty Boxes,” a meditation on the symbolism of coins, why coins are not the same as money, and why they have the potential to contain powerful symbolism but only if the performer invests them with “the value and poetry of what we put inside.”

The author’s own essay, “Treasures and Other Magic,” discuses a story by Alvaro Cunqueiro, in a book entitled Tesoros y otras magias (“Treasures and Other Magic”), which inspired Piedrahita’s work in his personalized approach to developing original coin magic. He goes on to consider the differences between card magic and coin magic, including all the many opportunities for effects and plots that playing cards provide and which coins do not. (He is also an excellent card worker as television spots on YouTube will attest, but he appears to have a particular passion for coin magic.) And he addresses the fact that, among the myriad of methods available to cardicians, there are few if any self-working or automatic coin tricks, and that “…the most basic technique with coins is vulnerable. In coin magic there are no infallible techniques.” These are important and significant issues for magicians attempting to do magic with coins, issues that are longstanding but all too frequently ignored, and at the performer’s peril.

Finally he considers the benefits and hazards of using coin gimmicks and fekes. This issue is further examined in the third essay, “Fakes, Gimmicks, and Other Stories,” by Manuel Cuesta, who cautions that, “Only a small percentage of magicians makes [sic] an appropriate use of this double-edge sword.” And to avoid these pitfalls, Piedrahita recommends “that you bring out the shell only when everything in Bobo has already danced through your fingers.” I could not agree with him more, yet I seem to meet fewer and fewer students who have truly worked through The New Modern Coin Magic, or make the effort to first master material done entirely with ordinary coins, before moving on to the complications inherent in incorporating mechanical technology.

Coming from Piedrahita, this advice takes on great significance to those paying attention, because in fact, almost every trick in the book requires some kind of special equipment; and what’s more, Piedrahita is in the habit of using the most sophisticated (and high-priced) such devices currently available. But he also quotes Tamariz’s comment that “a good antonym to the word ‘art’ could be the word ‘easy’,” meaning that the purpose of the added technology should never be based on making the work easier, but only to make it truly better. Relying on a gaff to seemingly make the work easier is more often than not a case of self-deception that ignores the demands such tools present to the performer. (If I may be forgiven for recommending my own work, I refer you to my own essay about this subject, "Gaffs versus Skill," in my book, Preserving Mystery.)

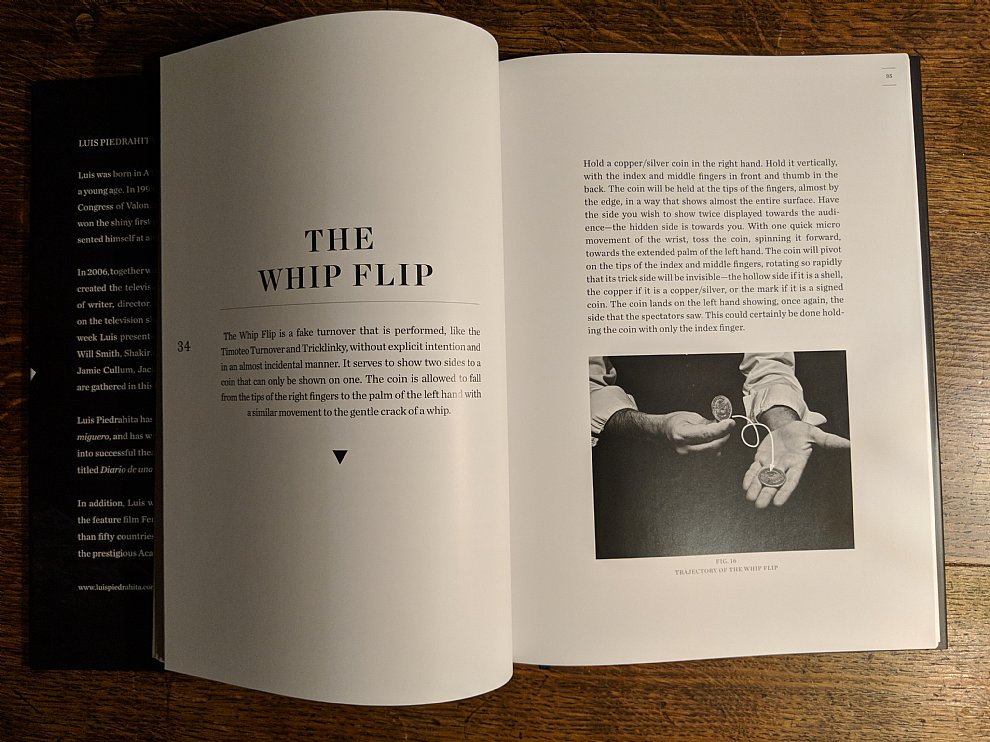

The technical descriptions begin with Part 2 of the book, which describes five “very personal moves” of the author. That description acknowledges that these tools work particularly well for him, but may not suit everyone, and that since “All magicians’ hands are different, therefore, from time to time, they create their own very personal moves.” This is an idea that does not appear very much in the literature of coin magic in particular or sleight-of-hand magic in general, but is well worthy of thoughtful consideration in making decisions about one’s own technical choices. Four of these techniques are essentially subtleties of sorts, which address various strategies for suggesting that coins are solid and ordinary, without explicitly saying so. However, one of these techniques, the Pinky Toss, is a whole ‘other deal’, as the saying goes.

In brief, this demanding sleight is a Han Ping Chien variation in which the switched in coin comes out of Tenkai Pinch. It is a thing of significant difficulty but also exquisite deception if properly executed. And while it is among the most difficult sleights in the book—likely the most difficult—it is appropriate to mention that this is not a book for beginners. Not only do you need to possess a skill level varying from intermediate to advanced, depending on the routine (with perhaps one exception), there are also times in which the author’s technical descriptions are minimal, and assume prior knowledge and understanding. Thus, for example, Geoff Latta’s One-Handed Turnover Switch, albeit a well-known move among coin workers, is not described but only referenced, as are several other such techniques. This isn’t mentioned by way of complaint, but only that the student should be aware of what to expect.

The author puts his Pinky Toss to use in the first two routines, a three-phase Copper/Silver transposition, and a technically demanding but extremely clean four-coin production. This latter piece begins with a brief commentary on how magicians often trivialize the extraordinary effects of magic. This is indeed a commonplace problem that others have commented upon as well, and late in the book, Jorge Blass presents a brief essay on the subject, pointing up not only its importance, but also examples of Piedrahita’s ability to point up the power of every “magic moment.”

Next comes Piedrahita’s radical approach to that holy grail of coin magic, Ramsay’s Cylinder and Coins. The author’s handling is eminently practical and simplified, which is not to say it is easy. But regardless of whether this appeals to everyone’s personal tastes, my favorite element of this is his substitute for the cork. Others have used these props – a toilet paper roll instead of a leather cylinder – but the rest of the solution is quite clever.

Coins Through the Table is the author’s version of Dai Vernon’s classic Kangaroo Coins, and this is the one routine that does not demand much in the way of advanced sleight of hand technique. But the construction here is excellent and worthy of any performer’s consideration.

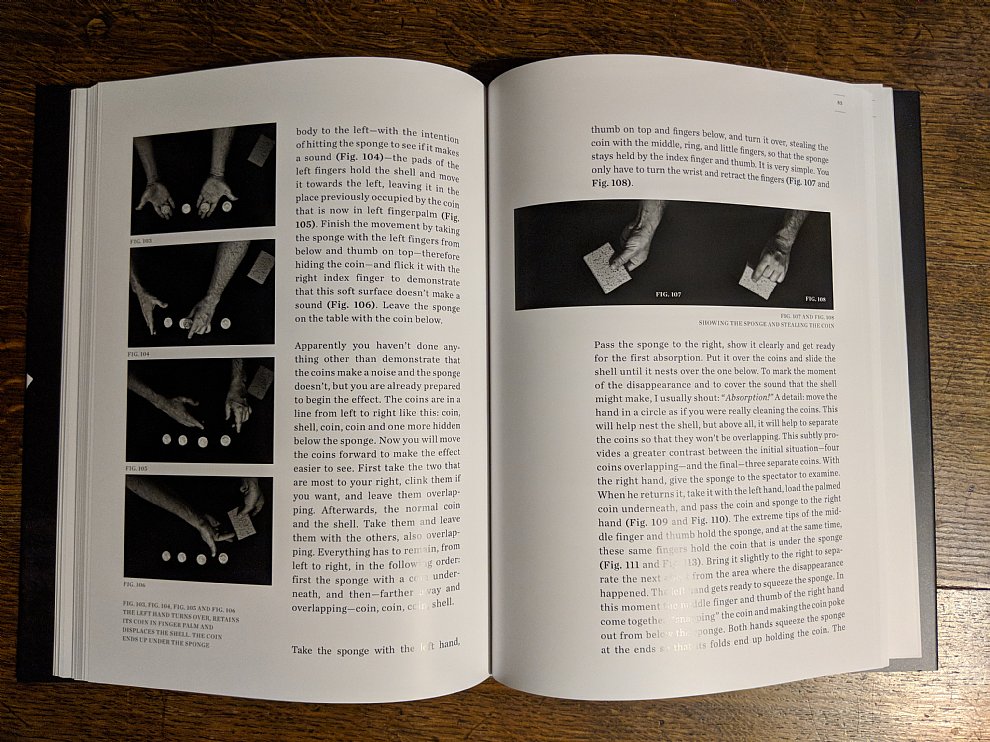

Four Coins and a Sponge is an offbeat routine that, in the Rothian tradition, applies a new prop to the limited effects of coin magic. In this case the starting point, that most missed when first published by Michael Ammar, belongs to Doug Bennett. Briefly, coins are progressively soaked up or “absorbed” into an ordinary kitchen sponge, and then “squeezed out” – a series of surreal variants on a sequence of coin vanishes and appearances.

Coin in Aspirin is another oddity in which a marked coin vanishes and then visibly and gradually appears from an Alka-Seltzer tablet (or equivalent) as it dissolves in a glass of water.

Signed Coins That Fly From One Hand To Another is a Coins Across routine that utilizes a principle that the author believes “is the best idea in this book and one of the best that I’ve ever had.” I certainly will not contest that claim. The principle is a brilliant application of a clever gaff, and the effect that results is a test condition routine, perfect for television—a point to which I will return shortly.

Wild Coins, the Homunculus Effect is the author’s handling, based on a Roman Garcia idea, for the Wild Card plot done with coins, previous versions of which have been published by David Roth, Al Schneider, and Geoff Latta, among others. Coins Through Handkerchief is the visual penetration of two coins through a semi-transparent handkerchief. And the book concludes with a detailed description of another novel routine, Coins and Bubble Wrap, a production of four coins followed by a Matrix plot in which the coins are covered with two small squares of bubble-wrap, but remain shockingly visible throughout as they progressively transpose.

Every routine in this book is distinctive in its methodological choices and especially the resulting effects to which these methods are applied. These routines are in many ways particular not only to the author’s artistic tastes, but also distinctly to his professional demands. He is a television performer with “name” standing—not just a random magician doing a spot on a talk show—and he not only has a reputation to uphold, but he needs to achieve a potent impact amid demanding conditions not only of live-on-tape television, but standing side-by-side with internationally renowned Hollywood celebrities. He requires absolute attention and tremendous impact.

And with these routines, many of which are novel in plot and most of which are demanding in method, he achieves these noteworthy goals. That’s what these tricks are built for, featuring startling visuals, remarkable clarity and cleanliness, and astonishing impact. And if you assume that the technical demands have been mastered – a challenging assumption to make, to be sure – then in fact, the methods are extremely practical, generally lacking angle problems, and so are in essence, in the author’s words, “bulletproof.” He writes, “The potency of the magic must be indisputable.”

Which means, frankly, that they won’t be for everyone. Coin magic—because it is “object magic” that depends on the fundamental sleight-of-hand requirements of “simulation” as dubbed by Dariel Fitzkee—is uncompromising in its technical demands. If you do sleight of hand with coins at a level of 99 percent towards an imaginary goal of perfection, or 98 percent or 97 percent, or perhaps even 95 or 96 percent—you’re good.

Once you fall much below that 95 percent level, most coin magic turns to shit. I use the word advisedly. Don’t kid yourself.

That’s one challenge to meet in general with coin magic, and in particular with advanced coin magic like much of what’s in this book’s pages. Another is that these routines are very difficult to effectively present. The author advises in his opening essay that, “…coins are ideal for the kind of magic that requires a symbolic presentation halfway between reality and fantasy.” And while he cautions about the dangers of muddling coin magic with too much metaphorical “goop” (I’m dying to know what the Spanish word for “goop” is), his personal manner of performance is very difficult to achieve. He manages to imbue the magic with just enough presentation to lend it emotional, poetic, and above all mysterious qualities, but he never seems to overdo it. I have seen much magic of many sorts, not only coin magic, weighed down with presentation to the point that the mystery and delights of magic come crashing to earth with dismal results.

And yet presentation is a particular challenge for coin magic, for several reasons. Much of successful coin magic relies on a savvy sense of rhythm and pacing, and what Vernon called “punctuation.” These are difficult facets to pin down, but without them, both the appeal of coin magic and the effectiveness of its methods can be easily damaged or demolished. By the same token, the effects of coin magic are frequently highly abstract and intellectual, and are therefore difficult to attach meaning or emotional impact to. I’m not sure I’ve never seen a presentation for Wild Coin that made sense or mattered much to me as a viewer, except in the most intellectual of contexts.

Luis Piedrahita manages to overcome these challenges in his style and persona—a character, he offers, that is as unique to every performer and as “non-transferable as a set of false teeth.” And he has created a demandingly pure approach that is particularly suited to television and other venues that he frequents. Is the Signed Coins That Fly From One Hand To Another a trick you’re likely to use in your next strolling magic gig? Well, as it happens, this is one of the few routines here that you could probably apply in that setting without too many insurmountable challenges. But even then—do you need the test conditions of this routine when you’re performing in that setting? Will you be able to seize sufficient focus so as to warrant an appreciation of the potential impact?

That is an artistic question I will leave to students to ponder. And if you consider the formal plots for which David Roth is renowned, it’s clear that this is not the first time these questions have been asked and answered, at least by a rare few. Few magicians may ever perform Roth’s The Tuning Fork, but in the right conditions, it is a spectacularly artistic piece of work.

One cannot deny the truly wondrous and magical quality of Coins and Bubble Wrap, or the uncompromisingly pure machismo of Signed Coins That Fly From One Hand To Another. In essence, this is as much a book about theatrical coin magic as it is about technically advanced coin magic. I doubt I will be working on much of this material myself, but your mileage will sure vary, depending where you find yourself along your own personal path. More importantly, I found this book filled with challenging ideas, clever plots and methods, and scintillating magic. That it is beautifully produced in large format simply helps to further bolster the essential gravitas contained within the delights of its contents. And too, this is clearly a caring translation that effectively captures and transmits the voice of a unique artist.

This is a substantial book about how to make powerful and beautiful magic with coins. And that, surely, is saying a lot.

Coins and Other Fables by Luis Piedrahita. 12” x 9” hardcover with matte dustjacket; illustrated with 200 black-and-white photographs; published by Conjuring Arts; 2017. Price: $59. Available from the publisher.

Bonus Clips

I believe that all of these clips are drawn from the aforementioned talk show, “El Hormiguero,” and all of these routines appear in Coins and Other Fables. Expand the browser, turn up the volume, put aside the smart phone, and experience this magic as it all but demands to be experienced.

Lyons Den Collection