A Celestial Celebration

ADELAIDE HERRMANN

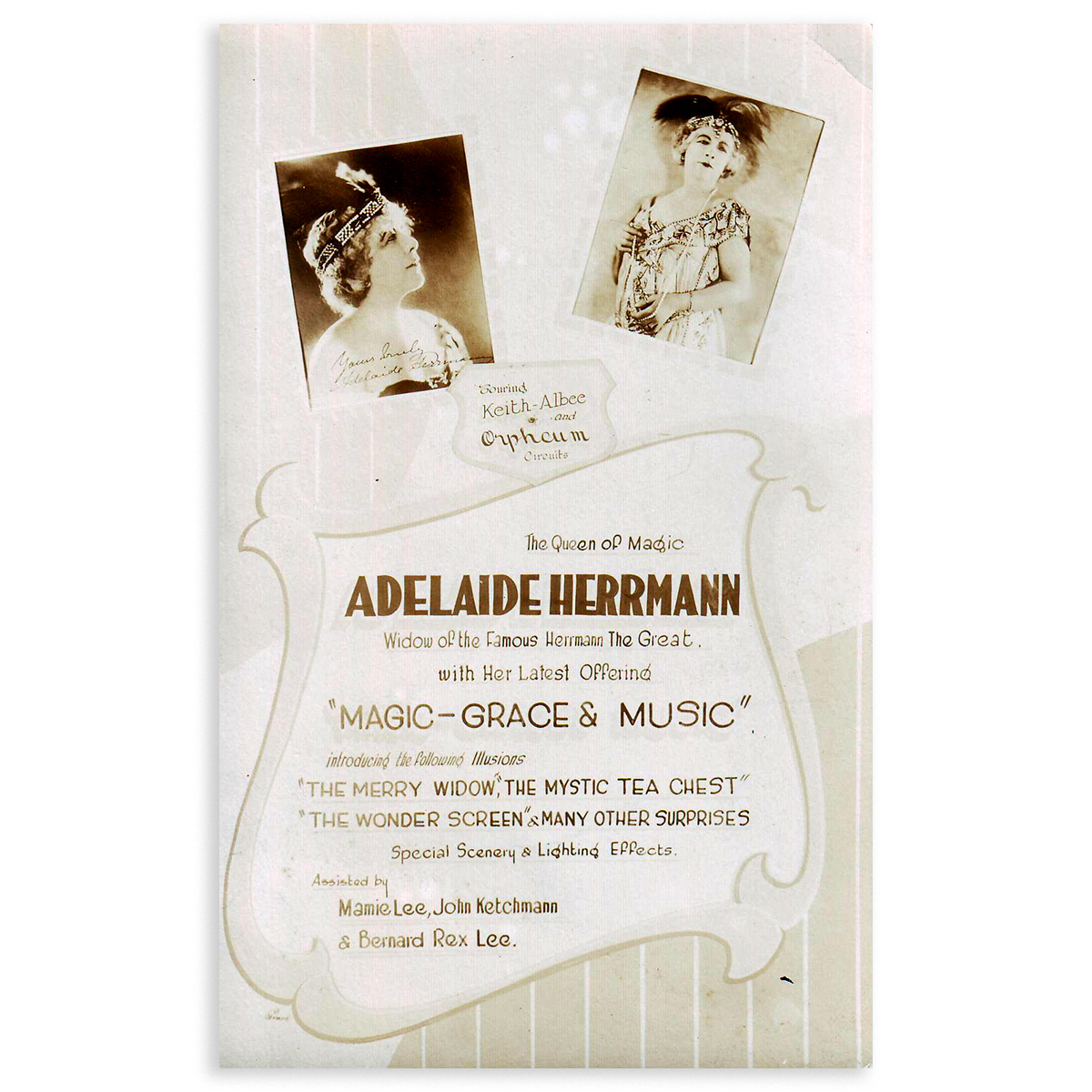

“Queen of Magic”

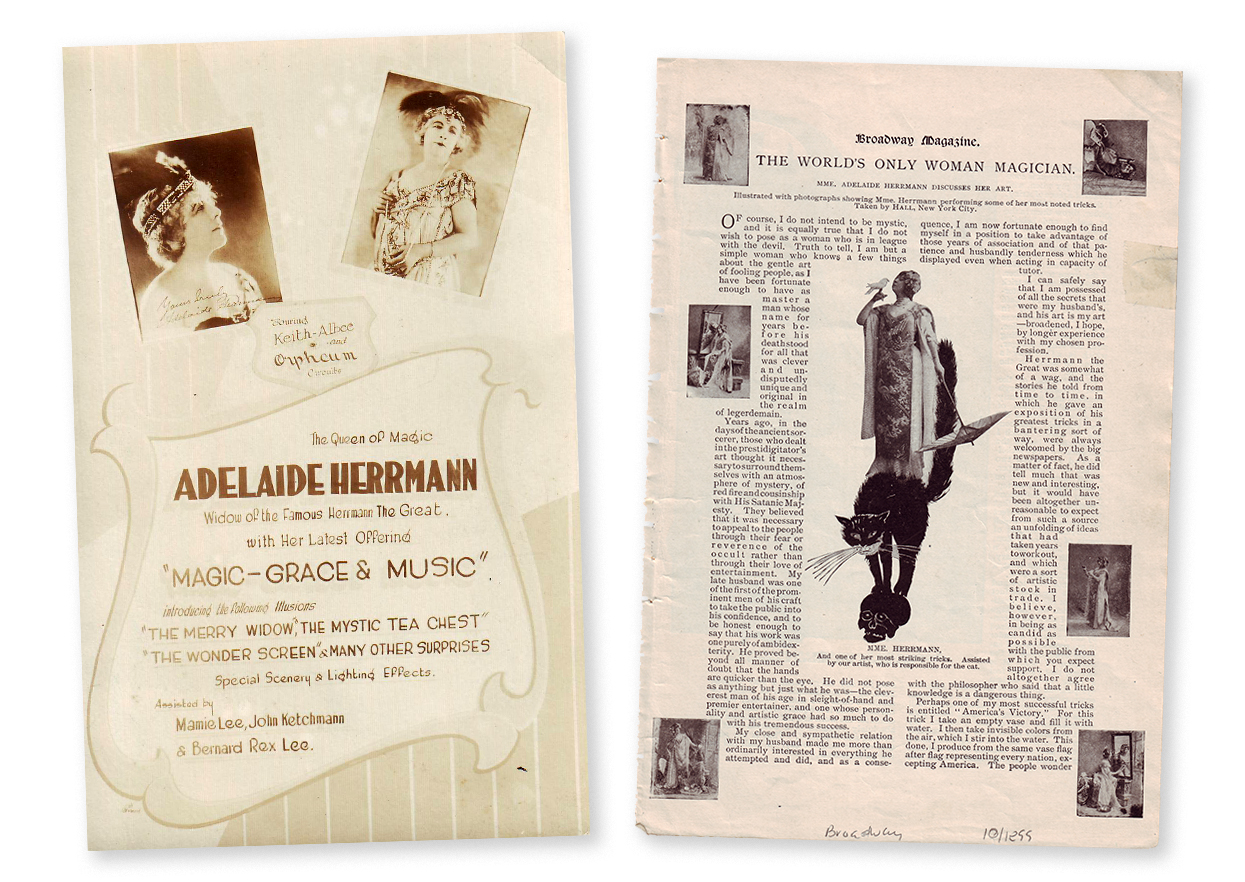

The magic dealer Joe Berg (1902-1984) was once interviewed about famous magicians he had seen. When asked about Adelaide Herrmann, Berg admitted he had seen her in vaudeville in the ‘20s, but he shrugged and said, “She was just an old lady doing magic.” Yikes. Could he have been just a bit more dismissive? Twenty years as the lead assistant to a legendary magician and thirty years performing on her own—what does a woman have to do to get respect? Well, Berg’s opinion aside, it’s clear that all female magicians who came afterward stand on the shoulders of Madame Herrmann (1853-1932), whose lavish stage show was graceful, elegantly costumed, and mysterious. Plenty has been written about the “Queen of Magic,” but I cannot pass the letter “H” in my series without giving her once again the credit she deserves.

“Big events” may not be all that frequent in the world of research into female magicians, but 2012 was a banner year. That’s when Margaret Steele published Adelaide Herrmann’s memoir, which had been “lost” for eight decades. In the last few years of her life, the doyenne of magicians had been writing a book about her career with and after her husband. Occasional mentions in the magic press of this work-in-progress were tantalizing, but when she passed away in 1932, the book remained unpublished. For years, no one knew where it was, how complete it was, or if it even existed at all. But as it turns out, a 295-page typed manuscript, edited by a woman named Stella Grenfell Florence, had been passed down in the family of Herrmann’s niece, where it still remained in the 21st century.

Margaret Steele speculates that the book was never published because Adelaide was a “victim of her own longevity.” When she died at age 78, the legacy of Alexander Herrmann was a distant memory, and perhaps publishers felt “her shelf life had expired.” Not knowing the extent to which she or her heirs attempted to get the book into print, it’s impossible to say how well it might have sold at the tail end of magic’s so-called golden age. But magic historians had long wanted to read it, and I was thrilled when it appeared in 2012 as Adelaide Herrmann Queen of Magic: Memoirs, Published Writings, and Collected Ephemera, compiled with notes by Steele.

I had previously written a modest profile for my “Women in Magic” series in The Linking Ring for January 2007, which appears below, with additions based on Madame Herrmann’s writings. While Steele admits that the memoir is “self-flattering and incomplete” (focusing mostly on her legendary husband and giving only five chapters out of thirty to her own solo career), Adelaide is a wonderful storyteller. As the key witness to much of the Herrmann legacy, she shares information not found elsewhere, and in a polished and engaging style.

The short version of her career is this: Born in London to Belgian parents who were not in show business, Adelaide Scarsez snuck off at the age of fourteen to join a Hungarian dance troupe, keeping her dreams of becoming a dancer secret from her family at first. While on tour in New York she received romantic overtures from a comedian named Gus Williams, who gave her an engagement ring. Adelaide returned to London without making a firm commitment and, coincidentally upon her return, she went to the Egyptian Hall to see a magician who was in the middle of an historic one-thousand-night run in the pre-Maskelyne era of that famous venue. The son and brother of magicians, Alexander Herrmann (1844-1896) had apprenticed himself to his brother Compars at an early age, but had now established himself as a major celebrity. During the performance, the handsome, dark-haired conjurer asked for a volunteer to loan him a ring. Adelaide consented, and her ring went up in flames, only to reappear tied around the neck of a dove. She didn’t realize it at the time, but that was the end of Gus Williams, and the beginning of a grand adventure with Herrmann the Great.

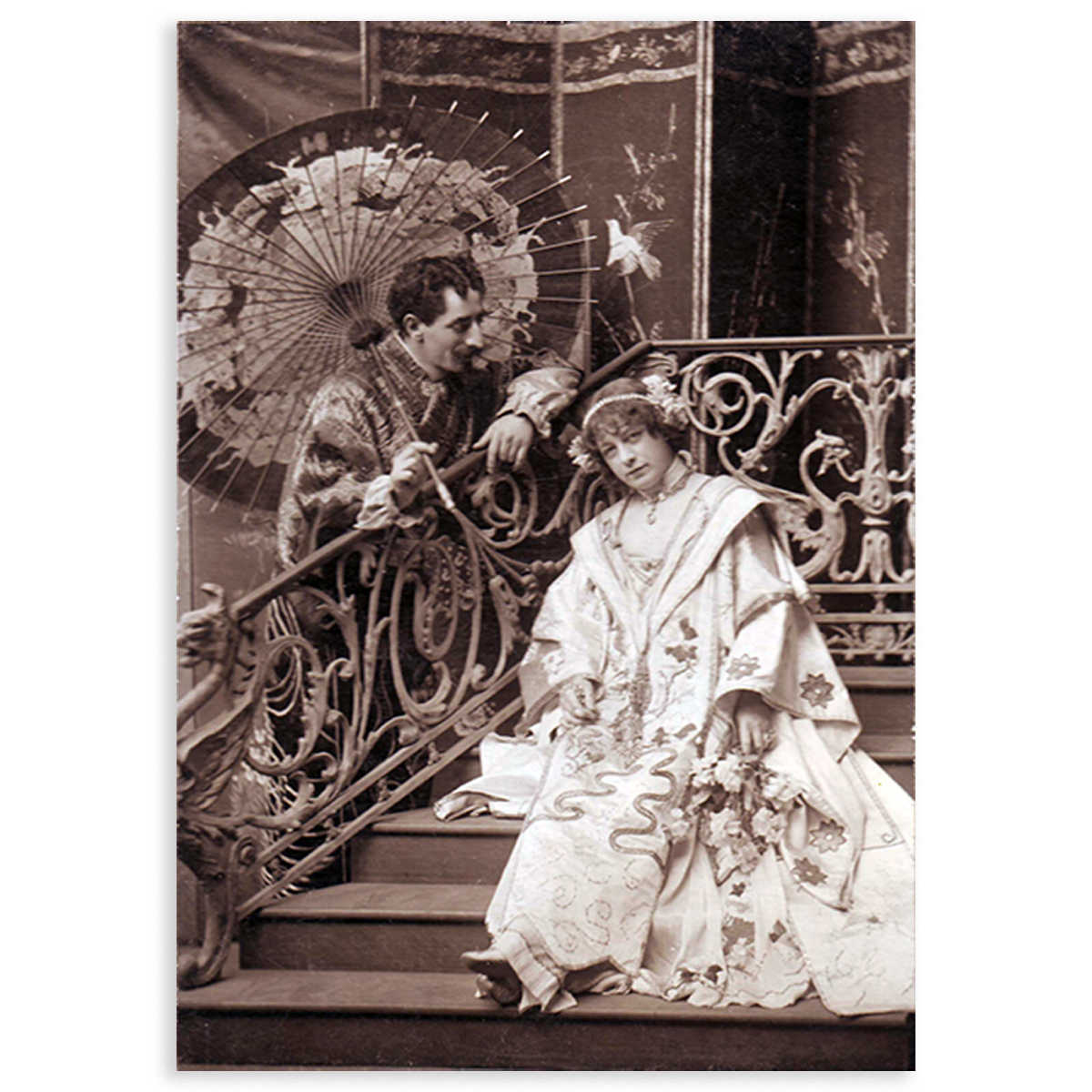

She soon joined a troupe of lady velocipede riders, developing yet another strenuous stage skill. When the troupe sailed from England to New York in 1874, who was sailing on the same boat? Naturally it was Alexander. The two renewed their brief acquaintance, which soon developed into a romance, and within a year, they were married at City Hall by the Mayor of New York. Fittingly, Alexander paid for the marriage license by producing “a roll of bills from his Honor’s flowing beard.” The new bride soon learned her husband’s act, and assisted Alexander onstage for the next 21 years. She was Trilby to his Svengali in the levitation act, she was shot out of a cannon on occasion, and her elaborate Serpentine dances were a popular feature of their show. Together they toured the world in style, making friends with royalty and celebrities and spending money lavishly. Despite competition from his rival Harry Kellar, the genial Alexander remained the leading magician of his era, equally dazzling with impromptu feats on the street or with miracles on the stage, all delivered with urbane witty banter.

But when Herrmann died of a heart attack in 1896 before finishing the theatrical season, Adelaide needed money to pay creditors. Turning down Kellar’s offer to buy the show, she embarked on a two-year tour with Alexander’s nephew Leon (1867-1909), who strongly favored his uncle and was a skilled magician, but who had the impossible task of filling legendary shoes. Reviews were mixed, though Amy Leslie of The Chicago Evening News wrote that “The Herrmanns are brave, all of them, and Leon has nearly fifty years to fight for his uncle’s supremacy.” Sadly, he did not. Adelaide’s tour with Leon ended in a clash of personalities, and he returned to Paris, where he died only ten years later in 1909. Meanwhile, the great magician’s widow had begun what was to be a nearly thirty-year solo career on the vaudeville stage. Yet her lavish lifestyle was over, the New York mansion she had shared with Alexander was sold, and, as Margaret Steele put it in a 2008 lecture, Madame Herrmann “lived in hotels and on trains for the remainder of her life.”

She called herself the “Queen of Magic,” but she could also be called the Grand Diva of Magic. Jim Steinmeyer humanized her story by throwing light on her sometimes caustic personality in his biography of Chung Ling Soo (who worked with the Herrmanns). She could be harsh. In 1895, the New York Times ran a story titled “Mrs. Herrmann Tried for Assault.” She later sued two nephews who dared call themselves “Herrmann the Great,” and—reading between the lines of The Sphinx—it’s clear that magicians sometimes walked on eggshells to avoid offending their elder stateswoman. Yet in fairness, most of the male greats were temperamental backstage, too—think of Kellar and Houdini, for instance—and Madame Herrmann genuinely had the respect of her peers. She and Emma Reno (wife of Ed Reno) were the two female magicians most consistently praised in the magic press during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Both received kudos without the condescending qualifier of being called “good, for a woman.” And both were well past fifty as they trod the vaudeville and Chautauqua stages.

On her own, Adelaide Herrmann had brief success overseas. She played the Winter Garden in Berlin in 1901, the London Hippodrome in 1902 during the coronation of King Edward VII—where her performance of the “Flags of all Nations” ended with a huge Union Jack—and the Follies Bergère in Paris, also in 1902. Following that, she mostly toured vaudeville theatres in the United States. Two attempts at full-evening shows were short-lived; vaudeville was her true home. She played the headline theatres and was popular with audiences even though much of her magic was standard—dove pan, flowers from cones, crystal casket, suspension, duck production, flag vase, and the Lady in Cabinet illusion. But her presentation was first class, and she expanded her act to include Ashrah, Noah’s Ark, and other feats.

As Margaret Steele notes, “She was not an innovator of tricks. Her talent was in reframing existing magic into exotic spectacles.” The oriental kimonos and parasols of her “Night in Japan” act in 1898, the lavish draperies in her “Cagliostro” act in 1910, and the classy settings of her “Magic, Grace & Music” act of 1926 all reflect her adaptability and high production sense. She bravely performed the bullet-catch during her first performance with Leon, even though she had seldom been able to watch as Alexander did the trick. Instead of using a wand, she preferred a more feminine prop, the fan. In his notes on a 1901 performance in Chicago, Peter Graef praised her deft use of her assets in her “very smooth and graceful” performance of the billiard balls: “The shell went south in a bosom servante!”

She was also willing to try new things—even if she sometimes failed. In 1911, she spent a fortune creating props and costumes for a Salome dance, based on the Oscar Wilde play and including a huge papier mache head of John the Baptist. It was never performed, as theatre managers balked at the sensual and avant-garde idea. Adelaide was in her fifties at the time.

Adelaide Herrmann kept performing until she was seventy-four, even springing back in 1926 after a New York City warehouse fire destroyed her show and memorabilia and killed most of her Noah’s Ark animals. What the fire didn’t burn, thieves took from the scene. Harry Blackstone came to her aid and loaned her props, and Madame Herrmann soldiered on for a year or so until she suffered a collapse. She retired in 1928 and died four years later of pneumonia and hardening of the arteries, on February 19, 1932. She had been fiercely dedicated to her husband’s legacy, and one of their former assistants, an elderly Black man named Milton Everett, one of the famed “Boomsky” actors, sat quietly wiping tears from his eyes at the funeral and was overheard to say, “A golden age of vaudeville goes with her. And there are few enough who remember it now.”

Madame Herrmann & Dell O’Dell

As I researched my book on a later “Queen of Magic,” Dell O’Dell (1897-1962), I was struck by just how much in common she had with the earlier holder of that crown. If I can be forgiven for shamelessly quoting from myself, here is an excerpt from Don’t Fool Yourself: The Magical Life of Dell O’Dell (2014) that discusses the personal and professional connections between these two remarkable women, with a few additions in brackets:

Dell O’Dell would eventually become the leading female magician in the United States—and one of the most successful magicians of either gender in the century. She didn’t start out that way, of course, and she didn’t even start in magic with an original act. But her timing was perfect. By the time she stepped on the stage as a comedy magician in September of 1929, the three most prominent women in the business were no longer on the scene. [Madame Emma Reno (1867-1927) had recently died, and the “Queen of Coins,” Mercedes Talma (1868-1944), was retired.]

By 1928, Madame Herrmann had completed a remarkable career. She had traveled all over the world with her husband, meeting celebrities and world leaders and assisting Alexander in his performances. Grief-stricken at age 43, she had been forced by debts to resume his magic show in 1897, returning to the stage a little more than a month after he died of a heart attack. Stepping into the shoes of a beloved showman was painful and difficult, but Adelaide dove in with courage. She even performed a daring bullet catch on the inaugural tour. It was one of Alexander’s signature feats, and the one that frightened her the most when he performed it. Her show—which also briefly featured Herrmann’s nephew Leon—became a showcase for her grace and creativity. From her elegant dances to beautifully staged illusions, Adelaide gave the public a spectacle of choreography, costumes, and mystery. And she did it for thirty years.

In a pleasing bit of historical symmetry, not only was Dell O’Dell born in 1897, just as Adelaide Herrmann was beginning her own career as a magicienne, but Dell began her own profession in magic only a year after Madame Herrmann ended hers. The reigning Queen of Magic announced her retirement in April of 1928 from the stage of Keith’s Orpheum in Brooklyn. There was no official or immediate passing of the mantle to Dell as Kellar had done for Thurston; the two pioneering women were simply passing in the night. And though Dell’s first magic act was nothing like Herrmann’s performance, at least one reviewer made the inevitable comparison:

Few women have garnered anything like real success in the realm of magic, but one exception is Mme Herrmann, widow of Herrmann the Great. It is more likely, however, that one young female might find the field more fertile than have the predecessors of her sex. She is Dell O’Dell. It is said of her that she knows a lot about magic and is already proving her worth as an exponent of deception and mystifying feats... Some of her offerings are serious, but most of it is on the burlesque order… So far over the RKO circuit her success has been encouraging.

No doubt the association was flattering to Dell, but the reviewer could not have known how deep the connections between these two women ran. Professionally, their performance styles were very different. Adelaide emphasized spectacle and fantasy and never spoke onstage, while Dell would develop a brash, comic style with rhyming patter. Yet personally, the two had much in common. Like Dell, Adelaide had been fascinated by acrobats as a child and wanted to imitate them. Both women performed in another line of entertainment before taking up magic. Adelaide had been a dancer in the famous Hungarian Kirafaly troupe and a trick cyclist in Professor Brown’s Lady Velocipede Troupe in the 1860s and ‘70s, all before she married Alexander in 1875.

The connections go even further. Both women would marry European showmen: Alexander Herrmann was born in Paris, while Charlie Carrer was Swiss. Both women lived for much of their careers in New York, and neither had children. Both adored animals and lived with a menagerie in their homes. Both were hospitable and loved to entertain, yet they also enjoyed practical jokes and fitted their homes with surprises for visitors. Both had specially-built vehicles that could accommodate guests—Dell loved her custom-designed trailer in the 1940s just as much as Adelaide had loved her private railway car that had been built for Lily Langtry (which she had to give up after Alexander died). [Both were savvy businesswomen and knew how to promote themselves. They even shared an assistant. The illusionist Roland Travers (1881-1970) assisted Adelaide and later worked for Dell, entertaining her with anecdotes about his previous boss.]

[Margaret Steele’s introduction to Adelaide’s memoirs points to even more similarities. When she notes that Madame Herrmann could be “charming offstage, but when crossed her fits of temper were famous and fearsome,” she was also describing the mercurial Dell, who sometimes took her frustrations out on her husband Charlie. Margaret also highlights Madame Herrmann’s skill in “reinventing herself,” an adaptability shared by her successor.] Both women got heavier as they aged but refused to let their girth define them. Not surprisingly, both continued working as long as humanly possible. Madame Herrmann was still performing at nearly 75. Dell took a booking on the way to the hospital as she was dying at 64.]

There is no record of Dell ever meeting her distinguished predecessor, or even seeing her perform. But Dell certainly admired Adelaide Herrmann and kept a photograph of her in her scrapbook. No doubt she felt a spiritual kinship with the pioneering conjurer. They both knew what it was like to adopt a profession that was largely seen by the public–and many of their colleagues—as a man’s role. Possessed of an irrepressible talent and desire to perform, both women made their own way and earned the respect of their peers. Just as Madame Herrmann became a sort of Grand Dame of the profession in her later years, feted by her fellow magicians until her death in 1932, Dell would also become accepted as “one of the guys.”

A version of this article originally appeared in the January 2007 issue of The Linking Ring and is used here with permission. It is supplemented with material from my book Don’t Fool Yourself: The Magical Life of Dell O’Dell, published in 2014 by Squash Publishing of Chicago. In addition to Adelaide Herrmann’s newly published memoirs and Margaret Steele’s introduction and notes, I also drew on the late James Hamilton’s excellent article in the August 2000 issue of Genii.

Stargazing

Here, in roughly alphabetical order, are several other women in magic whose names start with “H.” Elizabeth Haag (1876-1928) escaped from restraints along with her husband George. Setsuko Hanajima has been a pro magicienne in Tokyo. Pat Hannum (1931-2004) was the first female president of Ring 76 in San Diego. Lillian Hanson assisted her famous husband Herman, and Dolly Harbin performed as a pro before becoming an assistant to her zig-zagging mate Robert. There is also Canadian Teresa Hatfield, partner to illusionist Murray Hatfield.

The Belgian magicienne Ann Hardy (1921-2005) worked as an assistant to her husband and on her own, winning the FISM 1st prize for women in 1952, while Andrea Hardy is a German magician, juggler, unicyclist, and Chaplin impersonator. The famous actress Rita Hayworth (1918-1987) assisted her husband Orson Welles on USO tours in the ‘40s, and Granny Harris (1894-1982) performed magic as a WAC in during the Korean War. Ruth Hathaway (1899-1970) was a partner to her husband in the ‘20s, then later teamed with Lester Lake. Miss Hayden was one of the earliest women in magic, getting her start in the US around 1839. Lynn Healy has done pro stand-up and had a business making topits and other fabric props. Janet Heath did magic in the ‘40s. Haidee Heller assisted her brother Robert in his nineteenth-century act.

Debbie Henning was the wife and partner to Doug for almost 20 years. Christy Henson is a graceful performer and past President of Ring 29 in Little Rock. Two other Herrmanns should be mentioned: Marie (1861-1916) was Leon’s wife and assistant, and Gladys (1895-1966) was the wife and onstage partner to Felix. Mrs. Carl Hertz (Emilie D’Alton, 1866?-1945) not only assisted her famous husband but also performed solo for a few seasons after his 1924 death. Hilda the Handcuff Queen broke free of jails in the US in the Houdini era, while Miss Hilden (1906-1994) did the same in Sweden in the ‘30s. Alyx Hilshey, a magician and busker from Vermont, was featured on the cover of Vanish magazine in 2021; and Kat Hudson was featured in the magazine Magicseen, also in 2021.

Not all female magicians were good performers. When a Madame Hoffman was reviewed in The Sphinx, the writer called her act “Magic as bad as it can be.” Among true pros, though, Hisako and Nana Hitomi both have performed magic in Japan. Donna Horn has garnered attention using magic themes as a confectionery artist in New Jersey. June Horowitz (1913-2018) holds the distinction of being the first female International President of the IBM in 1987-1988. She was still interested in the magic community at the age of 105. Beatrice Houdini (1876-1943) needs no introduction, but Miss Houdiny was an Austrian escapist named Dagmar Enzfelder, who performed with her husband Oskar. Lulu Hurst (1869-1950) was “The Georgia Wonder” in the 1880s with her then-novel strength-resistance act, and Minola Mada Hurst (1883-1962) rode the “magic kettle” craze in England circa 1905. Finally, Mary Louise Hurt (1913-1995) billed herself as “the South’s Leading Lady of Magic.”