In last week’s Take Two #23, about the Linking Rings, three of the performances I posted were by performers who originally honed their routines as street performers (and who, in some instances, still perform on the streets today), namely Tom Frank, Whit Haydn, and Chris Capehart. And so it occurs to me that perhaps it’s time to discuss this particularly challenging form of magic, and offer some examples of great street performers.

In order to avoid confusion in terminology, however, I must begin by defining some terms. Until David Blaine’s first television special, in 1997, the term “street magic” was universally used by magicians to mean “busking,” the traditional form of street performance, in which a performer—be it magician, juggler, mime, living statue, or other—establishes a space on the street as essentially a stage, gathers a crowd by stopping and attracting random passersby (“builds the tip” in the jargon), performs a show, and then “passes the hat” or otherwise collects money from the audience. Magicians who were buskers were known for doing “street magic.”

However, that term took on a different meaning after Blaine’s TV special, in which he established a new way to shoot magic for television. By shooting magic on the street, which lent the magic credibility, Blaine paved the way, at long last, for television to feature close-up magic, rather than being essentially limited to featuring stage magic based on the Las Vegas showroom model, as had been done for 25 years or thereabouts by Doug Henning, David Copperfield, and others.

The nature of magic on television is a topic for another day, but ever since “street magic” became associated with magicians performing for television, the term has become a confusing one, and so “busking” and “buskers” make the matter somewhat more clear, even if these terms are not widely known, or seem a tad old-fashioned. The point is that a magician with a camera crew is most certainly not busking, because he’s not establishing a space, presenting a complete show, and then collecting money. In fact, in 2007 I wrote a lengthy essay for Antinomy, a limited circulation magic journal, entitled “In Search of Street Magic,” about the new wave of television street magic, examining whether or not the term described a genuine venue, or an imaginary form of magic that was limited to a handful of men being followed around with camera crews. A decade later that piece remains just as relevant to the discussion and definitions as it did when it appeared.

Performing on the street, no matter what the particular performance art, can be a brutally difficult form. The performer is battling for people’s attention, trying to control the performing space, attempting to keep people around for the duration of a show that might last 15 minutes or even as much as an hour, and then somehow talk them into giving money before moving on. And what’s more, the professional busker repeats this process over and over again throughout the day.

In 2007, the Washington Post mounted a stunt in which the world-renowned classical violinist, Joshua Bell, played his Stradivarius violin in a Washington Metro subway arcade. According to the reporter's story:

It was 7:51 a.m. on Friday, January 12, the middle of the morning rush hour. In the next forty-three minutes, as the violinist performed six classical pieces, 1,097 people passed by.” At the conclusion of the performance, he had collected … $32.17.

The piece won a Pulitzer. The story is certainly well told.

On the other hand, the exploit could also have amounted to little more than a hidden camera stunt for a reality TV show. Context counts for a lot—be it in music, or reportage.

Which is, in fact, the entire “lesson,” if there is a lesson, to be drawn from the story. Despite a lot of highfalutin snooty nonsense having been written about “pearls before swine,” and about people’s ability to appreciate beauty, or even to “appreciate life.”

Twaddle. The only real lesson, beyond the importance of context in understanding … anything … is that Josh Bell isn’t a professional street performer. Because if you put Chris Capehart in that subway arcade, he would have made a lot more than $32.17. I’d bet money on it.

That’s no knock on Mr. Bell. He’s not a street performer and doesn’t pretend to be. It’s a different skill set. I’ve met Josh, I’ve heard him play Bach’s “Chaconne” live, the piece he began his public set with that morning. He’s a brilliant artist. The entire world of classical music knows that, and has known it for a long time, even though he’s a relatively young man. (And at the end of this piece you will find a spectacular bonus video I am linking here for you enjoyment.)

But if you’re trying to make a living on the street, you not only have to master your art, you also have to master the very particular craft of street performing.

Early in 2013, I helped my friend, singer/songwriter/rock-star Amanda Palmer, write a TED talk entitled “The Art of Asking.” The talk went instantly viral, scoring a million views in ten days, and today tallies somewhere at about nine million. The talk led to her writing a book of the same title, published in 2014, which reached the New York Times bestseller list; I spent the first six months of 2014 bouncing around the country helping her to write the book, as an editor and creative consultant (or, as she dubs me in the book, her “book doula”).

In the talk and the book, Amanda describes her days in her first job as a professional performer after college: she spent about five years busking in Boston’s Harvard Square as a “living statue” dubbed the “Eight-Foot Bride.” As she describes it, “I would get harassed sometimes. People would yell at me from their cars: ‘Get a job!’ And I'd be, like, ‘This is my job.’ But it hurt, because it made me fear that I was somehow doing something un-joblike and unfair, shameful.” In fact, many people then, and even now, thought of street performers as little more than beggars with a costume. Readers of The Art of Asking often recount how the book has altered their assumptions about the nature of street performing as art.

Like I said: a brutally difficult pursuit. Performing on the street is similar in many ways to performing at trade shows, and performing as a Magic Bartender behind the bar. (At various times in my career I’ve made significant portions of my living in two of these venues; I’ve never worked the street.) You are performing for people who do not expect to see you there, and who have no obligation to give you their attention. And yet somehow, amid the vicious competition for that attention, you have to create a show. All three forms require both emotional and pure physical stamina.

Jeff Sheridan

Busking is an ancient craft; one of the earliest depictions of a magician performing the Cups and Balls on the street is “The Conjuror” by Hieronymus Bosch, painted in 1502. But busking was unknown on the streets of New York City in the late 1960s when magician Jeff Sheridan began performing regularly at the Walter Scott statue in Central Park. Street performers were often treated as criminals in those days, and were constantly harassed and often arrested by police.

Jeff is a remarkable performer, and considered by many to be one of the most skilled card manipulators of his time, as well as one of our most original conjuring artists. He profoundly influenced many up and coming magicians in the New York region, and he single-handedly pioneered the modern revival of street magic in New York City, establishing a trend that grew throughout the 1970s and into the 80s, followed by outstanding performers including Chris Capehart, William McQueen, and Cellini, among others. But Jeff’s style was unique: whereas busking magicians invariably work as speaking performers—loudly and constantly!—Jeff, dressed entirely in black, worked silently, without music or any other audible accompaniment. It is abundantly interesting to note that the only other performer working similarly by the 1970s was Teller, in his solo days long before encountering Penn Jillette, but the two silent performers discovered this performing mode independently, and long remained unaware of the other’s work.

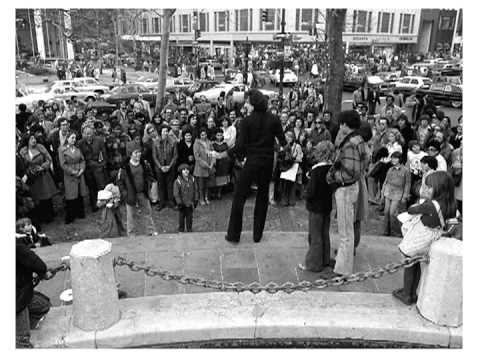

We have many photos of Jeff working the street, thanks largely to the 1977 book he co-authored with Edward Claflin, Street Magic. Although we do not have footage to show you of Jeff performing on the streets in those days, note the size of the crowd in this photo.

While we don’t have footage from that era, here is a clip of some of Jeff’s wonderful work:

Chris Capehart

As mentioned, in Take Two #23 I included a video clip of Chris Capehart performing his signature version of the Linking Rings, and I encourage you to please go watch that if you have not done so already. Chris is a dear friend, a longtime headliner at Monday Night Magic in New York City, a regular performer at the Magic Castle, and one of my favorite performers to watch. He was also another of the early street performers of the 1970s, coming out of Philadelphia and regularly performing in New York City—in fact, we first met on a Manhattan subway platform, lo these many years ago. He’s been a mentor to countless fellow street performers, not only magicians, but no less than to George Peterson of the legendary Otto & George, the filthiest ventriloquist act in history, that began as a street act. Chris can tell you hair-raising tales from the street, some of which I recounted in a feature piece I wrote about him for the December 2008 cover story of Genii magazine.

Although the quality of this video is not great, this can help give you a sense of Chris’s immense charm and great comedic timing. He does a lot with a little here, and I have seen him bring down the house on a huge theater stage with this one little prop. Turn it up, pay attention, and enjoy the Master Magician, Chris Capehart.

Cellini

Another legendary performer of that era of modern street performing was the man known simply as Cellini. He not only performed coast to coast but throughout Europe and the world, influencing and mentoring countless other performers along the way. His acolytes are legion, and his lasting presence is felt in the work of numerous street performers of his own time and beyond. Here’s a recording of Cellini on the streets of one of his truly home turfs, New Orleans, shot in 1985. His closing routine is one of the most iconic of the street magician’s repertoire, as effective today as it was in 1502: the Cups and Balls, a subject we will revisit next week.

Bonus Clip

Finally, here is a special treat that I encourage you to save for when you can put aside a window of 30 minutes to watch something unique and memorable. Josh Bell begins by playing the Vitali Chaconne (not the Bach), accompanied by pianist Nadejda Vlaeva, and then engages in a conversation about art and craft wth magician Eric Mead. The presentation, at the 2016 EG conference in Carmel-by-the-Sea, concludes with a magic performance by Mead, accompanied by Bell on the violin.

Next week, Take Two on Buskers of Magic continues with Part 2, including a sampling of contemporary performers, as well as the work of some non-magicians.

MORE: TAKE TWO ARCHIVE