I was saddened to learn last week of the death of John Cornelius, an award-winning close-up magician and brilliant inventor of original magic, whose star shone most brightly in the magic world in the Seventies and Eighties.

Born in 1948 in Lamesa, Texas, a whisper of his origins could always be heard in the gentle Texan drawl of this charming professional performer. As a young man, Cornelius picked up a college degree in air conditioning design (a career path he shared with Derek Dingle), but quickly switched to his first passion—magic—a field in which he would become internationally renowned and celebrated.

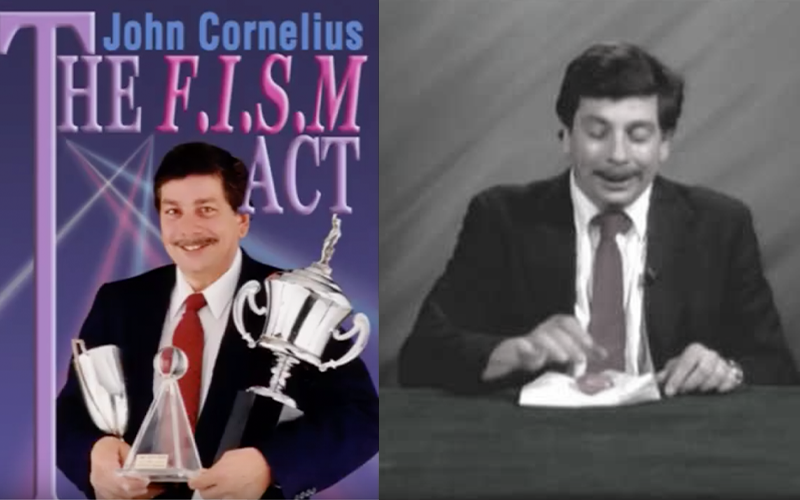

Indeed, at the 1979 FISM competition in Brussels, Cornelius took first prize in Close-Up Magic, possibly the first Americans to do so. He was also on the leading edge of the American invasion that would sweep top awards at FISM in 1982 at Lausanne with Americans Michael Ammar, Daryl, and Lance Burton, who each won Close-Up Magic, Close-Up Card Magic, and the Grand Prix, respectively. The Americans would continue their victory march in 1985 in Madrid with all three prizes in Close-Up Magic taken by Paul Gertner, Johnny “Ace” Palmer, and Michael Weber winning First, Second, and Third place, respectively. But most extraordinarily at that year’s contest, John Cornelius took first prize in Close-Up Card Magic, making him the first (and I believe only) performer in the history of the competition to be awarded first prize in both Close-Up Magic and Close-Up Card Magic.

Although contest outcomes are often dubious and debatable, no one ever second guessed Cornelius’s awards. He was a rare magical creator whose competition act was comprised almost entirely of originally invented methods—some of which also served as the workings of original magical effects. His record of invention is unmatched when it comes to innovative close-up magic. What’s more, Cornelius was not only a remarkable inventor of ingenious mechanical methods and secret devices, but he was also an accomplished sleight-of-hand technician and creator. Few in the history of magic could match him in the combination of these two categories of skills.

As an extremely popular convention presence of the era, you could rest assured that in seeing a Cornelius performance or lecture, you would be thoroughly fooled, and repeatedly so. It was a feat few magicians could duplicate, and an experience that I, and many of my peers, enthusiastically looked forward to at every available opportunity. John Cornelius was a master at fooling magicians. And often, when he explained those methods in a lecture, you would be both delighted, and astonished again, at the ingenious nature of the methods.

The standing joke at that time was: “What’s the first sentence of the instructions to a John Cornelius trick? Step one: Go to the hardware store.” Cornelius had a knack for creating methods that were extremely clever, practical, and often adaptations of commonly available materials. On the other hand, some methods, despite haven been explained for the published record in a book of John’s material—like for the production of a birthday cake, complete with lit candles, that would magically appear as the climax to his version of the Roy Benson Bowl Routine—were probably not duplicatable by ordinary mortals who lacked the necessary building skills.

While the following list will not be recognizable to the non-magicians in my readership, I must take a moment to provide a partial inventory of Cornelius’s inventions. It’s safe to say that every one of these items was a bestseller in its time, and unlike so many popular magic dealer items (especially these days), these were quality items that were actually worth doing, and thus were in use by countless professionals. These included:

- The Cornelius Nickel

- Rising Business Card Case

- Shrinking Deck

- Flash Die

- FISM Flash

- Pen Through Bill

There were many more such hits to his credit, and as a result, Cornelius would become a successful magic dealer with a unique line of items invented solely by him. His items were extremely popular, and included in the repertoires of countless magicians of the Seventies, Eighties, and beyond—this writer included. (The Flash Die was the climax of my dice stacking routine in my Magic Bartender days in the mid-to-late Eighties; and my version of his cleverly constructed "Borrowed Bill Routine" is described in the book, Switch, by John Lovick.)

But there was a painful downside to Cornelius’s unique contributions: the popularity of his clever mechanical inventions made him a prime target for copyists and thieves—often synonyms for “magic dealers and manufacturers.” While the world of magic has always struggled with thievery—a longstanding staple of some manufacturers, retailers, and performers as well—Cornelius’s cottage manufacturing business was a feeding trough for mass production predators. The phenomenon grew so pervasive and profoundly demoralizing that, by the late Nineties, Cornelius retreated from the world of magic. And thus, our art was subsequently denied the gift and wonders of his inventive mind.

I recall attending a national convention of the Society of American Magicians—I believe it was 1996 in Las Vegas, albeit I’m not absolutely certain. I realized, in walking through the dealer’s room (a major feature of any magic convention), that multiple dealers were offering clearly ripped-off, unauthorized copies of Cornelius’s fabulous trick, the Pen Through Bill. Appalled and offended, I approached various members of the SAM hierarchy, eventually finding the man who was in charge of the dealer room, and made my objections known.

Of course, the outcome of my attempts were nil, and unsurprising. Magic organizations are ever eager to go to battle to fight so-called “exposure”—the publication of magic methods to the public—on the grounds that this is an “ethical” issue. Of course, as Teller points out, “No one ever died over the method to a magic trick,” and the fact that it is generally preferable for magicians to conceal our methods is not an ethical issue (other than perhaps the potential argument that in some rare cases it can cause other performers economic harm), but rather a theatrical issue. As Michael Weber so elegantly states it: “We don’t keep secrets from you. We keep secrets for you.”

But while magic organizations are quick to fight pointless, juvenile, and invariably doomed battles over “exposure” (apparently unaware that the history of magic’s growth and literature is a history of so-called “exposure;” anyone who doubts this fact should consider the origins of Hoffman’s Modern Magic, often referred to as the most important conjuring text of the late nineteenth century), such organizations are historically loathe to enter into the one ethical arena in which their strength-in-numbers could actually have a positive impact: namely, theft of intellectual content, by performers as well as manufacturers and dealers. But magic organizations have never shown the slightest willingness to enter that particular fray, mostly because when one considers the cost of advertising in their journals and magazines, and for renting dealer spaces at their conventions, the results of such principled conflicts might cost them actual money. In other words, ethics are great—unless there’s a buck in it.

And so, the story of John Cornelius’s fabulous inventiveness and creativity is a sad lesson for the magic community—albeit a lesson few have learned or pay attention to. A notable exception was the late, truly great, Denny Haney—a magic dealer who called out every thief he encountered, and refused to put a copyist’s products on his shelves. In fact, if you were a frequent copyist, Haney would refuse to stock any of your items; he simply wouldn’t do business with you at all. We may never see his likes again.

I hope this digression may provide some interesting insights for non-magicians into the subculture of magic, albeit while noting that these issues, ever so briefly summarized here, are controversies that have long raged in the magic world. No less than David Devant, perhaps the greatest magician Britain ever produced, and certainly one of its greatest of the Edwardian era, was kicked out of the famed Magic Circle for “exposure.” It is to laugh.

But I provide this commentary out of respect for the life and wondrous work of John Cornelius. Meanwhile as a personal aside, one of my favorite and funniest memories of John Cornelius is of a coin trick, and its supposed method, that he performed for me at the New York Magic Symposium in 1982. Unfortunately, the method is a part of the story so I can’t repeat it here, but if you’re a magician and cross paths with me sometime, do ask me for the anecdote, and we’ll share a laugh in memory of John and his infinite cleverness.

And so, while it is a shame that John Cornelius eventually all but abandoned marketing his original magic creations, nevertheless, his name and work live on in the awards and acclaim he received, in the countless friends he made and who remember him and his magic— in a book for magicians that records many of his methods (albeit not much more than that), and also—not insignificantly—some of the timeless sleight-of-hand maneuvers he created. The Coin That Falls Up, the “Deal Set” flourish (made famous by Bill Malone’s iconic version of the Sam the Bellhop routine), and the Cornelius Fan Steal are effects and methods still in use today, and will undoubtedly remain in use for many years to come.

I’m lucky to have seen the magic of John Cornelius up close and in person, and on numerous occasions. And I’m truly sorry, and saddened, to acknowledge that some of my readers will never have that experience—but I will try to show you a brief taste of such wonders now. Farewell, John—and thank you, always, for the magic, the mystery, and the laughs.

John Cornelius’s “Fickle Nickel” was one of his early magic successes, and it’s likely the only close-up trick ever used to open two network television specials in the days before cable—as well as a British TV special. Here, Doug Henning starts his 1975 “World of Magic Special” with this trick. Keep in mind that this was done live for a huge television audience. It’s a wonder his hands aren’t visibly shaking.

This video rapidly shows John Cornelius demonstrating six tricks in briefly cut performances, and presents some idea of his creativity. Most of these items are based on classic effects, but John brought his unique inventiveness to each and ever one of them. And then there’s the cigarette, which I still remember thoroughly flummoxing me the first time I witnessed it.

Finally, John Cornelius’s award-winning FISM card act was facetiously titled “Every Card Trick in the World in Under Ten Minutes.” It was an eccentric collection of methods and effects that probably no other performer would ever attempt to duplicate.

MORE: TAKE TWO ARCHIVE