Book Review

“The rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated.”

—Mark Twain

Paraphrasing Mark Twain, it appears that rumors of the death of the magic book have been greatly exaggerated. While it’s true that print runs have in general been significantly reduced from what they were ten or twenty years ago—perhaps an indication that younger magicians are not reading books or magazines as much as their elder predecessors, preferring to rely on video as their primary resource—nevertheless, looking over my own admittedly select reviews in the past year, I have had the pleasure of reading books like Luis Piedrahita’s Coins and Other Fables, Woody Aragon’s Memorandum, and John Lovick’s Handsome Jack, Etc. Having reviewed close to 500 conjuring books over the past twenty years or thereabouts, I can readily say that these titles are at the top caliber of the literature, books that are and will remain worth reading and rereading for decades to come. And I anticipate several more such quality works soon on the way, which I will be reviewing in the coming months as they are released.

And now comes Asi Wind’s Repertoire, a book densely packed with breathtaking material, capable of transforming any close-up worker’s repertoire from a gathering of tricks into a program of miracle mysteries. I daresay the majority of close-up magicians will readily improve their standard of work by adopting just one selection from Mr. Wind’s professional repertoire; adopt two or three such pieces and you will drive yourself toward matching standards that might well serve to raise the caliber of your work for the rest of your life.

Magic being a small community, I have so often been called upon the review the work of my friends that I rarely trouble to mention it; that reality virtually goes without saying, and it presents an ongoing challenge to a critic striving for fairness and objectivity. I have always tried to do so with honesty and integrity, risking the chips falling where they may. Most of the time those chips have fallen in good places, largely because my friends tend to do good work; occasionally because my friends are gracious artists and colleagues. Infrequently the chips and have fallen elsewhere, which generally serves to reveal much more about the subject than about the reviewer. C’est la vie.

In this case (and in fact in the case of several forthcoming works), I feel compelled to mention that in some sense I might well be an inescapably biased observer. I first met Asi Wind in Israel in 2000, when he performed on stage at a convention at which I also performed and lectured. He’s come a long way (and so has his costuming).

Subsequently, Asi emigrated to the United States, settling in New York City. After paying some dues in entry-level show business for a while, and working on mastering English, the former stage magician became interested in close-up magic, and early in that process, was exposed to and inspired by Juan Tamariz.

It wasn’t long before Asi auditioned for Monday Night Magic, the Off-Broadway show I have co-produced for twenty years now (along with my partners Todd Robbins, Peter Samelson, and Michael Chaut; the fifth founding partner was the late Frank Brents). Asi quickly became a regular performer at our show, where I had the opportunity to watch his relatively rapid development as an artist of some stature. More than a decade ago I came to consider Asi Wind to be, in his age group, one of the very best close-up magicians working in the U.S.

Over time, Asi graduated into a speaking stage performer, and became one of Monday Night Magic’s top headliners, and one of the busiest and highest paid performers working in New York. But he wasn’t done there. He now commands top fees in corporate and private events internationally, but only when he can fit in such work between the demanding time he spends working and performing with David Blaine, who pens a flattering foreword to the book at hand. Asi is a key figure in David’s creative brain trust, as well as touring with him on his recent American live shows, and performing a guest spot every night in the show, introduced by Blaine as the star’s “favorite magician.” He ain’t lying, and my introductory aside here is a long way of saying that Asi Wind is one of my favorite magicians too, as well as a close friend.

As such, much of the material in this book is not new to me, but that doesn’t render any of it any less exciting to at last see in print. In fact, it’s generally the contrary, because in a number of cases I’ve had the chance to watch this material develop from concept to finality, and I also read the book in several draft formations. All of it has come a long way from its starting points. And finally, some of this material I have used in my own work for many years.

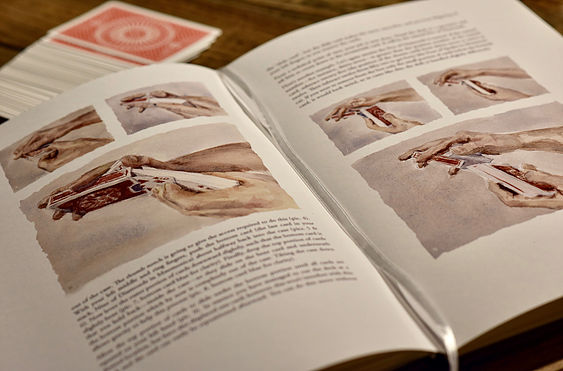

At 156 pages, this volume might seem a bit pricey to some potential buyers. I believe the book is well worth its asking price of $100 for several reasons. For sheer value in the quality of the content, amid 19 routines plus two useful sleights, the material is sold at good value considering that literally all of it is practical, audience tested, polished, and, in a word, stunning. It’s a book of truly astonishing, professional caliber material that is within the reach of intermediate to advanced students (and some of it is easier than that). And then add to this the fact that the book is a uniquely beautiful volume, a work of art in its own right, because the lovely high quality design is defined by the text’s unique accompanying illustrations, in the form of 111 original watercolor paintings by the author. The book is as lovely a physical object as is its contents. All this and, with the significant collaborative assistance of John Lovick, the writing is clear and efficient, cogently communicating a book in which every page is rich with ideas worthy of extended thoughtful consideration. This is not a book to rush through once and lay aside. It’s a book to study, to learn from, to challenge oneself with, to think about, to grow from.

Remarkably, every entry comes directly from the author’s professional working repertoire, and the material is presented not by genre or categorization of any sort, but simply in the order in which it was first created. Thus we can subtly detect the author’s innovative track record, while seeing how his creativity, thinking and experience have evolved over time.

Following Blaine’s preface, the author opens with a thoughtful preface about his life and history in the pursuit of artistic accomplishment. He recounts that “When people ask me if I am a painter I usually respond, ‘I paint.’” This anecdote leads to a valuable piece of counsel: “Here is perhaps the best advice I got from one of my early art teachers: Don’t strive to be a good artist, strive to be a better artist. Becoming a good artist has a final destination; becoming a better artist is an ongoing journey.” This perspective defines Asi’s nature, and it is a quality he shares with the best magicians I have known, including Tommy Wonder, who Asi cites as an influence and inspiration. “Tommy Wonder was not a good magician. Tommy Wonder was a better magician.”

Dai Vernon shared this trait as well. It is not egoless, and it is not falsely humble, but it bears a kind of artistic humility. Vernon always strived for perfection, while at the same time deeply recognizing that perfection was never achievable. This was what he tried to communicate to his acolytes, and why he didn’t trouble to record or publish every variation he created along the pathways of his exploration. But he tried to make things good enough to “stand the test of time” as Asi posits, and much like Vernon, adds, “And if I don’t achieve that, I will settle for just getting better.”

Many years ago, one night at the Monday Night Magic after-show gathering, Asi approached me and asked if I was familiar with a sort of origami trick published in 1958 by Will Dexter, in which a dollar bill was folded in such a way that it created the appearance of being two bills folded in quarters. I said that I’d seen it but never given it much thought; Asi said he thought there was something to it that had the potential for something greater.

And boy oh boy, was he ever right.

Eventually he created the opening routine of Repertoire, “Time is Money.” This trick, like several in the book, has been previously published, some as video downloads, some in lecture notes, but as Asi writes in the concluding lines of his preface, “…writing this book has made me rethink every one of them, and I’ve tweaked their methods, structures, and presentations. So consider these ‘software updates.’” Not only do these descriptions contain his latest work and thinking, but are also by far the most thorough descriptions published of any of the material that has been previously released.

If you are not familiar with “Time is Money,” the performer begins by borrowing a bill from a spectator, which the volunteer signs. In synch with the performer who offers their own bill as example, each folds their respective bills in quarters. The spectator holds both bills on his open palm; they are now retrieved by the performer, who then causes one bill to mysteriously vanish. The spectator is then directed to discover, to his or her great astonishment, their own signed bill under their own watch they are wearing on their wrist.

This routine is a fabulous piece of magic that, like much of the material in Repertoire, falls distinctly within the rubric of “packs small, plays big.” Indeed, while it is a practical miracle for use in strolling close-up magic, it’s also a feature of Asi’s stage act (which he elaborates upon with further effects in his stage work that are not provided in the book)—which means you can learn and develop the routine in close-up before eventually graduating to the stage with it. As with much of Asi’s material, the success of the routine is dependent on important elements of psychology, misdirection, and spectator management, and all of these details, along with critically important details of verbal management as well, are provided in this routine and throughout the book.

The next routine is another signature Asi Wind effect, his handling for which has already become a standard for many, namely his handling of “A.W.A.C.A.A.N.,” which stands for Asi Wind Any Card At Any Number. This neo-classic plot is, in my estimation, a fine example of what Charlie Miller used to refer to as “intrigue tricks”—meaning, plots that were intriguing, even fascinating, to magicians, but not necessarily to lay audiences. The reason for the intrigue is that the plot presents a uniquely puzzling challenge with countless avenues by which to achieve the desired outcome; the reason for the audience disinterest is that the effect is a purely intellectual one, only apprehended conceptually, with nothing visual, or visceral, in its impression on the audience.

But that hasn’t stopped magicians from generating countless methods, especially in the past decade or so, thanks to the current fascination with the memorized deck (a popular but not always required method for the plot), and the work of David Berglas and Juan Tamariz.

In short, I believe that Asi Wind’s approach to the “boxed” ACAAN is the definitive solution. A bold statement, admittedly, but one I do not make lightly. And I speak from personal experience, having seen him perform the feat countless times, and having utilized his method in my own work for many years.

Not long after I took a deep dive into memdeck work, about twenty years ago, I learned Tim Conover’s unpublished version of the boxed ACAAN. It relied on a memorized deck and a secret cut of the pack as it was removed from the box. Asi cites other published precedents, notably from Ken Krenzel and Alan Ackerman. When Asi shared his version with me, I adjusted my usage from Conover’s to Asi’s, which was similar but a bit more refined, thanks to his minimal but clever modification of the card box. He has since refined his handling even further, covering the secret cut even more effectively, and working out the details, in years of performance, of all the many small variations that might occur in real life application.

As mentioned, I’ve read and witnessed countless published variants on this plot, and I think “A.W.A.C.A.A.N.” beats them all by miles. When I see versions that require sometimes severe limitations in the available selections of cards or numbers, or worse yet, involve additional props like Post-It notes on the back of cards and the like, I turn the page, in somewhere between disinterest and disgust. “Unclear on the concept” is a frequently thought.

For those who came in late, the plot is this: The deck of cards is returned to the card box and tabled or handed to a spectator. One spectator names any card. Any card. Another spectator names any number. Any number. Either or both can change their minds until a final decision is made. The magician then removes the deck from the box, hands it to the spectator, who counts down to the named number, where the named card is discovered.

It’s not much to look at, but intellectually, it’s a squeaky clean impossibility. It’s that pure, that clean, that simple in appearance. I did say: this is, in my estimation, the definitive solution. No more calls, please, we have a winner—and we’ve had it for quite awhile.

Of course, the challenge is then to make the damned puzzle into an entertaining and engaging mystery. And I think Asi Wind might know more about that than all but a handful of other performers in the world. He has ways of exploiting it in impromptu circumstances, in professional close-up, and on stage as well. I’ve seen them all. And in these pages he describes in the most thorough detail many ideas about how to make the feat into an effective piece of mystery entertainment. He also provides much thought and practical advice on all the many contingencies that might arise, and how to deal with and master the mathematical challenges that intimidate some performers. These twelve pages amount to a manual on the subject of the ACAAN, and really, no others need apply. This is only the second entry in the book, and for my money, it’s the second example of a trick worth the book’s asking price to a working performer. In my book, Preserving Mystery, I include an essay entitled “Suiting Repertoire,” and recount several anecdotes when the perfect trick suited the perfect circumstances in the course of my career. One of those stories involves ACAAN. The method I used was Asi’s.

One more anecdote before we turn the page: Years ago at a MAGIC Live convention, I sat with Johnny Thompson to watch the close-up show, which included Asi Wind. It was one of the first times John was to see Asi work, if not the very first time perhaps, and Asi included his boxed ACAAN. I knew what was going on, since I had been using the handling for years, but John was completely fooled, and immediately said so to me. We discussed it several times, but I didn’t tip what I knew, because I knew John would want to think about it. Two weeks went by, and the phone rang. It was John. “I figured out what it had to be! I can’t believe I missed it!” In solving what had gotten by him, Johnny was even more impressed than before.

Moving on, as with the ACAAN plot, there have been many approaches to the Brainwave effect that do not require the standard gimmicked deck made famous by Dai Vernon. In “Out of the Blue,” Asi contributes a version in which any freely named card is discovered to possess the only odd-colored back in an otherwise ordinary pack. There are other similar approaches in print, including by Juan Tamariz, but Asi applies the standard elements, along with his own work on ACAAN, in distinctly practical fashion. Don’t overlook this miracle that delivers an impossibility and leaves you with an ordinary deck in your (and the spectator’s) hands.

The next two routines provide, respectively, a version of the “color sense” or color detection plot, and then a remote stop trick. Both of these classic plots are given clever solutions here that provide impenetrably mysterious results.

The author returns to the ACAAN plot again with “S.A.C.A.A.N,” an approach to ACAAN performed with a deck shuffled by the spectator. Inspired by, among other things, the work of Denis Behr, there are excellent ideas here if you want to achieve the feat with a shuffled pack. It’s too bad you won’t see it before you read this, because it would fool you badly.

Next comes “A Coin Trick,” which is in fact a clever card mystery based on Simon Aronson’s “Prior Commitment,” that reveals two selected cards under extremely clean and mystifying conditions. This comes with Asi’s superb presentational points, suggesting how to adapt the trick to spontaneous conditions, incorporating significant dates or other numbers unique to the circumstances or individuals involved. Pay attention to these details as it’s ideas such as these that reflect the distinct qualities of the creator’s vision of how to use every available opportunity in service of maximizing the mystery potential of conjuring.

Then comes “Double Exposure,” another neo-classic, this time using a cell phone. I’m not big on using cell phone technology for magical effects, for the rather obvious reasons that the technology is invariably suspect (and correctly so) as the source of the method. But there are exceptions, none in my estimation greater than this version of “Triumph” using the spectator’s cell phone camera. Michael Weber independently developed similar ideas for this plot, utilizing a copy machine, and David Blaine performed a version of Asi’s routine on one of his network television specials. The idea that an effect this memorably impossible can be performed impromptu is truly remarkable. In short, a card is selected and returned to the pack and the cards are shuffled face-up and face-down. The perform fans the pack and places it in the spectator’s hand, taking a photo with the spectator’s camera. The deck is briefly squared, then spread – the cards are still mixed haphazardly, facing both ways. When the spectator check his phone, he finds a photo of himself hold the fan of cards—except that the fan shows only all the backs of the cards, except for one face, which is his selection.

If you already do this trick, Asi offers three additional touches that enable you to show the cards facing both ways prior to the finale. All are clever and worthy additions that add to the conviction and clarity of the spectator’s experience. And of course, the spectator, at the end, walks away with permanent evidence and a physical memory of that experience. This trick, at the risk of invoking a tired cliché, is a reputation maker.

Next comes “Catch 23,” another “packs small, plays big” routine of mental magic designed for platform or stage. As the authors write, this routine “is essentially a Chair Test that doesn’t use chairs, combined with a Bank Night, in which the contents of the envelopes are related to the people onstage.” This is a remarkably clever routine that is rather simple to achieve with regard to the mechanical methods and props, albeit requires expert audience management skills. Asi often performs this on the David Blaine tour, and the routine delivers a profound and entertaining mystery for audiences that run into the thousands. After making fair selections, each spectator ends up with a prediction that speaks directly to his or her personal appearance or identity (that’s the Bank Night part), and the routine concludes with a clever and impactful final prediction regarding particular facets of the performance, including an inordinately clever way of revealing a prediction of the positions the spectators freely choose to take on the stage (that’s the Chair Test part without the chairs). The methods and plots have precedence but the combinations here are positively ingenious. This bare bones description doesn’t begin to do justice to the potential power, and especially the entertainment potential, of this smartly formulated routine.

“The Trick That Never Ends” is a clever card trick that can, as the author points out, make for a perfect close-up opener, in which a spectator cleanly and directly discovers his or her own selected card. This is a very commercial and practical little close-up trick.

Next comes “Torn, Marked, Stabbed, Crumpled, Burned & Restored Page.” This is another feature of Asi’s stage act, and yet another packs small, plays big stage miracle. A book test of sorts, related to the “Pegasus Page” plot, this a marvelous routine in which the spectator freely selects one of three books, freely selects a page, freely selects a word, whereupon the page is torn out and destroyed. The spectator then discovers that the exact page has now returned to the book, the selected word is clearly indicated, and the book is given away to the spectator before leaving the stage.

As with “Time is Money” and “AWACAAN,” Asi has worked out every detail of this routine through countless professional performances, and refined it into a fabulously practical and clean mystery. Although there are a number of principles involved, at its core lies an extremely clever book switching device that he invented years ago and first applied at a performance at Monday Night Magic. Before the show that night, Asi drew my attention to the routine, and the fact that he had added a brand new idea that I should watch for. I didn’t see it, and neither would you. The incredibly clever principle in fact has wide application and any performer using a prepared book on stage would be wise to consider the use of this device and its many potential applications.

Following “Make No Mistake,” a dual color change invoked for the revelation of two cards, comes “Crossing Over,” Asi’s version of the classic “Biddle Trick.” This invariably commercial plot sees new life in Asi’s hands, in which he applies an extremely fair and deceptive initial process for the spectator’s selection of the card, that comes from the work of Chan Canasta. This is a practical and mystifying close-up effect that any thoughtful performer can readily put to commercial use, and one of my two favorite contemporary approaches, the other being that of Jon Armstrong’s. Comparing those two different versions comprises an interesting lesson in differing visions and different points of emphasis within the same plot, each creator making their own distinct choices for their own clearly thought out reasons. I recommend the exercise, which might well help to clarify your own individual vision along the path of becoming a “better magician.”

“Reverse Engineer” is another piece that Asi tipped to me years ago, another ingeniously deceptive close-up card plot. That plot is simple and direct: The spectator is asked to freely name any card. He is handed a pack that he takes below the table, out of view. He removes any card from anywhere in the pack, reverses it, and returns it anywhere within the deck. After cutting the cards a few times he brings the deck above the table. The deck is spread and one card is reversed: the named selection. The deck is prepared. The trick is an impenetrable mystery.

“Supervision” is yet another packs-small-plays-big miracle, one of Chan Canasta’s most famous plots, in which the spectator, holding a deck of cards behind his back, removes two cards and places them in two different pockets, whereupon the performer identifies the cards, and the spectator identifies whichever pockets in which each resides. Johnny Thompson first brought this plot to my attention decades ago – he saw Canasta perform it multiple times when they were both working the Playboy Club circuit in the 1960s – and I began working on it when I first became serious about memdeck work. I have performed my own version countless times on stage and in close-up in the past twenty years, and despite my own extensive experience with the piece, and my own theories about how to do it, I found Asi’s thinking, approach and experience to be enlightening and thought provoking. So will you, and all the more so if you’ve never performed the feat before but considered attempting it. He also includes a unique element in which the spectator, with the pack behind his back, removes the first card from top or bottom, but then removes the second card from anywhere in the midst of the deck. I suggest you read that again and pause to consider the implications. This piece comprises yet another fine example of Asi’s deep insights into the amalgam of plot, method, presentation, spectator management, psychology, and verbal and physical misdirection that add up to turning tricks into memorable and utterly mysterious experiences. It’s a lesson worthy of any conjuror’s study.

Next come two original sleights, a secret card fold that takes place within the spectator’s view and under cover of fanning and squaring a pack; and a clever and deceptively casual card force.

“Not So Straight Triumph” is an incredibly commercial plot that delivers impact way out of proportion to the effort required to achieve it. Based on John Bannon’s neo-classic “Play It Straight (Triumph),” Asi has added a second phase to an already powerful routine. One spectator selects a card and pockets it without seeing its identity, and a second spectator selects a card, shows it around, and returns it to the pack. The performer splits the pack into four packets, shuffling them in various face-up and face-down combinations. He then spreads the pack to reveal that all the cards are now face down except for 12 cards of a single suit—let’s say Hearts—arranged in numerical order. The one card missing from that order turns out to be the Heart that resides in the first spectator’s pocket.

Now for the follow-up, the selection is placed aside, the deck is shuffled face-up and face-down again. The second spectator names his card, a Spade. The deck is spread, revealing that only 12 cards remain face-up, all the Spades, in numerical order, missing one. The first selection is now discovered to have magically changed into the second selection. It’s rare that a trick this good can be improved this much, but that’s exactly the case here. Learn this one piece and you will have a practical commercial routine that will consistently deliver a devastating impact.

We now return to the ACAAN plot once more, with “S.C.A.A.N.,” another shuffled approach in which the deck is completely shuffled (whereas in the previously described “S.A.C.A.A.N.” the appearance is that of a completely shuffled deck, but in fact a quarter of the pack is kept out of the spectator’s hands during the shuffling process). In order to achieve the genuine full deck shuffle, the plot is turned into a “chosen card at any number” rather than a named card, but truly, you can’t have everything, can you? Yet the approach here is an excellent one, based on principles we’ve learned by now from the versions previously described.

“Lucky 13” is a plot that dates back to Hofzinser’s “Suit Selection,” in which “[s]everal people pull small groups of cards from different parts of a shuffled deck, and those packets are randomly stacked. After a spectator is asked to name one of the four suits, the performer turns the cards over, and they are the thirteen cards of the chosen suit – in numerical order.” That prosaic description doesn’t do justice to an intriguing and mystifying routine, in which order is mysteriously created out of a very convincing case of chaos.

The final routine is “Echo,” a close-up card effect performed with two ungimmicked decks. Asi tipped this to me when he first came up with it, and I’ve used it on multiple occasions. The plot, which he first ad-libbed as an “out” to a trick gone awry, is one I find particularly appealing, as it unfolds in a manner that is perhaps less than obvious at first, but as the meaning comes into focus, you can literally watch the impact take hold as the sensation passes across the spectator’s eyes. I love that experience.

In essence, two decks are introduced, one red backed, one blue backed. The spectator chooses a deck, and then that deck is presented with the faces of the cards in view, and the spectator selects one of these face-up cards. The remainder of the pack is turned face down—let’s say this is the red deck—and the card is inserted face-up within the spread.

You now triumphantly announce that, “Your card is the only one facing up.” The spectator’s response is along the lines of “So what? I just saw you put it there,” whereupon the performer replies, “Yes, but I don’t mean in this deck. I mean the other one.” You now remove and spread the blue deck, whereupon the spectator’s card is the only one found to be face-up among the face-down blue backed cards.

You then turn over the two reversed cards. The card in the blue deck has a red back; the card in the red deck has a blue back. As the saying goes: BOOM!

Thus concludes a truly remarkable collection of material—truly an entire repertoire of professional caliber magic. Interestingly, this final entry is not the strongest trick in the book; it’s not the one with the most elaborate or original methods. But it is the last trick because it is the latest trick, and reminds us that its creator has doubtless already moved on to his next new addition to his own repertoire, even while we recognized that he will certainly come back and revisit some of these polished routines in the pages of this existing Repertoire and somehow perhaps manage to further improve a few with an additional touch or finesse, here or there. This is as it should be. This is how we become not merely good, but better. There is no doubt in my own mind that Repertoire, by Asi Wind with John Lovick, can and will help you to become a better magician. What more could a reader possibly want from a book of conjuring? For me, it’s more than enough.

Repertoire by Asi Wind with John Lovick. Hardcover with color plate inset and foil stamped titles; 156 pages; illustrated with 111 original watercolor paintings by the author + 2 black-and-white photographs; 2018; published by the author; Price: $100. Available online.

Lyons Den Collection