In December of 2017, I wrote Take Two #52, featuring Dai Vernon, by far the most important and influential sleight-of-hand artist of the twentieth century. Take Two #66 featured Juan Tamariz, the closest person we have to a contemporary Vernon, and another artist who has had a profound impact throughout the magic world, particularly on the card magic of our time.

These two men have influenced both the craft of magic—its techniques and methods—as well as the art, that is the performance of magic, far beyond any other individuals of their respective and overlapping eras.

But if we were to slightly adjust the lens through which we examine a particular creator’s impact on card magic, another name would also quickly into focus—and that name would be, Ed Marlo.

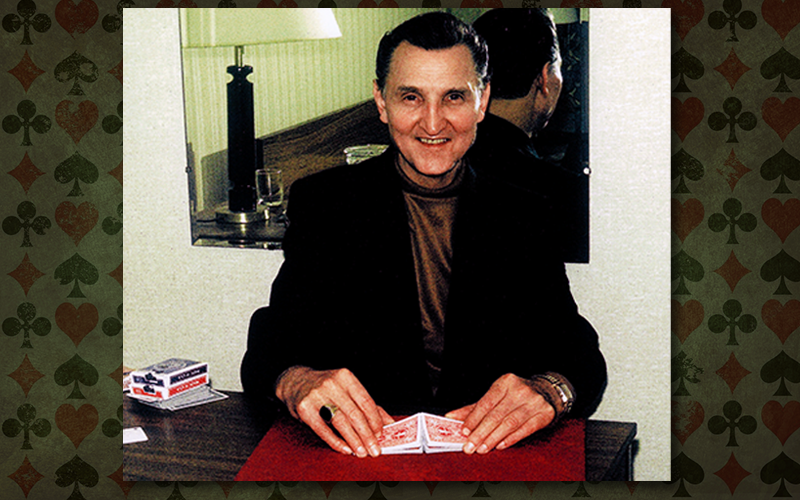

Born in Chicago in 1913, Edward Stephen Malkowski would eventually make his living as a tool and die maker. But as “Ed Marlo,” he would become famous in the world of magic as an obsessive examiner and practitioner of card magic—albeit, not as a performing entertainer.

The history of magic is filled with a litany of such notable amateur innovators, such as the Victorian card maestro Johann Nepomuk Hofzinser, whose influence is still at work today in the hands of countless card magic aficionados. I have written elsewhere that often, “amateurs create, professionals select.” Some of the greatest innovations can come from amateurs, but it’s not until professionals select what material that is most valuable, and put it before the eyes of both the public and other magicians, that the larger magic community recognizes the strengths of such material.

Malkowski’s first published contributions appear in The Tops magazine in 1937, and his first three items that appeared in that magic journal—in 1937, 1938, and 1939 respectively—were attributed to Edward (Marko) Malkowski. But his first booklet, Pasteboard Presto, appeared (in either 1938 or 1940) under the Ed Marlo byline, and that would forever after remain the name that Marlo published under—and in voluminous quantity.

Marlo was nothing if not prolific, to which this bibliography of seventy books will serve as certain testament. That list excludes countless journal contributions and marketed tricks with accompanying manuscripts, as well as Marlo journal contributions, and books written by Marlo’s frequent amanuensis, Jon Racherbaumer. In total, such contributions number in the thousands.

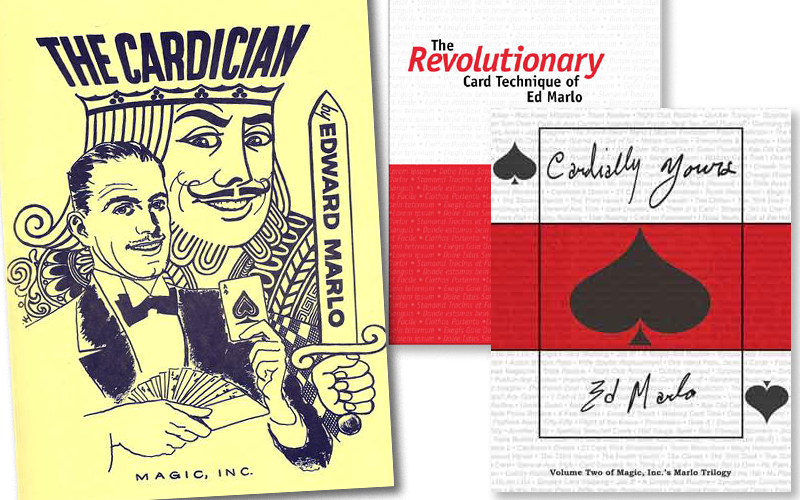

And with the title of his 1953 book, The Cardician, Marlo also gave practitioners of sleight-of-hand card magic a term for themselves that remains common parlance today. We are, indeed, cardicians.

Just as Vernon was surrounded through much of his life by students and acolytes, both in New York and then later in Los Angeles, where he became the mentor-in-residence upon the opening of the Magic Castle in 1963, Ed Marlo served as the center of the Chicago magic scene when it came to sleight-of-hand card magic. Although he was not a professional performer, in the Sixties Marlo did serve as a demonstrator on Saturday afternoons behind the counter of a Chicago novelty and magic shop called Baer’s Treasure Chest, where he took commonplace over-the-counter dealer items (including inexpensive, so-called “slum magic” items) and turned them into deceptive sleight-of-hand mysteries. Much of this work appeared in the 1997 book, Arcade Dreams, by Racherbaumer, which records much of Marlo’s non-card material.

But magic with playing cards was Marlo’s true passion, and it is not in the slightest hyperbolic to call it his obsession. One of his many acolytes, David Solomon, said, “I believe that he thought about card magic all his waking hours.” [ref: The Card Mysteries of David Solomon by Eugene Burger, 1997.] Solomon—at whose wedding Marlo served as best man—also said, “He wanted to invent every method possible …” And to this end—an impossibility, but a genuine obsession—Marlo would not only spent countless hours developing and refining endless technical variations, but he would, in turn, record every such variant and idea. As Solomon also said: “… I don’t think he could differentiate which were his best solutions, so he published them all.”

While I don’t wish to get too “inside baseball” here, I would be remiss if I failed to mention the controversies that repeatedly swelled around Marlo’s name when it came to crediting. Marlo was consumed by the notion of credit, and while few in his immediate orbit would go on record (Solomon being a rare exception, thanks significantly to Eugene Burger’s having been the somewhat odd choice to have written the book quoted from above), disputes eventually became a commonplace late in his life and thereafter. Such issues are important to magicians and our literature—entire websites are today devoted to excellently exploring and documenting such records—and at an elite gathering of cardicians I once witnessed such a dramatic and emotional presentation by a creator who had been a significant victim of Marlo’s credit predations that I will truly never forget it. Indeed, in the one and only “session” I had with Marlo, I ended up with a similar experience, made all the worse because it was another creator’s item that was plucked from me (a story for another day). And a thorough record of at least one such plunder can be found in the correspondence between Marlo and the great innovator Herb Zarrow, which is recounted, in lawyerly detail, in the pages of Zarrow: A Lifetime of Magic by David Ben. As the late Johnny Thompson once said to me (speaking of a notorious Marlo/Racherbaumer book): “The Shank Shuffle is a work of fiction.”

Partly because of this acquisitiveness, paired with the overwhelming volume of published items and variations, it was imagined by many, particularly during the explosive period of card magic creativity of the Seventies and Eighties, that there was some sort of competition between Marlo and Dai Vernon. While it is possible that Marlo may have viewed their long-distant connectedness in this way, it appears that Vernon gave it little concern—and for a number of reasons. One was a fact that what many bystanders often overlooked, namely that the two men were not contemporaries, Vernon being almost a generation older. Another facet was that while Vernon cared about credit, it was not only for himself; names like Nate Leipzig and Max Malini, the subjects of entire books in the Vernon literary oeuvre (penned by Vernon amanuensis Lewis Ganson), would be mere footnotes today, instead of being regarded as giants in the pantheon of magic, were it not for Vernon’s obsessive attribution and generous sharing of credits.

Finally, Vernon was always seeking the best versions of his work, but cared little for recording every step along the way. His constant seeking of improvement was neither aspirational nor acquisitive. His greatest competition was himself.

Eventually, late in Marlo’s life, when he would be welcomed to the Magic Castle and celebrated on stage alongside Vernon and Vernon’s longtime friend and colleague, Charlie Miller, Vernon would refer to Marlo as a “talented young man,” and greeted him with grace and generosity. History will note that Marlo enjoyed the recognition in the course of his Los Angeles visit. (And for magicians, video footage of a question-and-answer session during that period—an impromptu lecture of sorts held at the Magic Castle—recently came to light, and is now commercially available, produced by Vanishing Inc.)

But it would be a mistake to allow Marlo’s entire reputation to be reduced to this admittedly troubling issue. The fact remains that there is not a “cardician” alive who doesn’t use some bit of Marlovian technology in his work at some time or another. When I began to study his work in detail, in my late teens, I eventually worked my way through every “chapter” of the Revolutionary Card Technique series—actually a series of fourteen independent manuscripts that were not gathered into a single volume until 2003, despite having originally been published from 1954 through 1962. The complete volume of that collection, it is fair to say, comprises a landmark work, and I would recommend it to any budding card magician as a suitable place to begin study of Marlo’s vast output. But as David Solomon wrote in Marlo Magazine Volume 3, “Do not try to read the book like a novel from cover to cover in one night.” (I also recommend, for students looking for guidance as to how to approach studying Marlo’s work, this brief but useful “Edward Marlo Study Guide” penned by Andi Gladwin of Vanishing Inc.)

To say that Marlo’s publications were spare on production values would be a laughable understatement. The prose was terse; the print was more often than not generated by a typewriter (thanks to Marlo’s ever-hardworking wife, Muriel; the pair first met in grade school); the accompanying line drawings were simple but invaluable in helping the reader to make sense of the dry prose. The six volumes of the so-called Marlo Magazine, published circa 1976 through 1988, were massive comb-bound tomes, each one numbering more than three hundred 8½” x 11” pages of such densely challenging content.

Truly such tomes were far from user friendly, yet I pored over every page as each volume was issued. I can’t say that today I use a lot of the specific elements of what I learned—a sleight here, a finesse there, even fewer plots or presentations—but studying Marlo helped to teach me to think, with great care and detail, about card magic. Marlo provided invaluable instruction in how to analyze the work, how to choose between fine points and variables, in ways that still affect my thinking and analyses today.

It was noted Vernon acolyte, Bruce Cervon, who perhaps put it best to me, one evening years ago at the Magic Castle. He was explaining a trick to me, and mentioned a Marlo move—one of those fundamental Marlo techniques, or at least technical refinements, that remains in widespread use. Jokingly, I interrupted him. “Ah-ha! So you use that Marlo stuff!” And we laughed, but then Bruce offered perspective on the Vernon/Marlo comparisons of the era: “You know who Marlo is? He’s the guy in a white coat working in the laboratory.” Vernon is the orchestrator, Bruce went on to say, the guy who takes that work out in the world and puts it to use.

But another facet of Marlo that is often overlooked—because only a small fraction of his readers ever got the chance to see him work—is that he was a superb technician. He practiced as relentlessly as he studied and recorded, and he was able to execute, in scintillating fashion, a remarkable catalog of sleight-of-hand technique. Some of the films came to light long after they were shot, and today we can more readily find some of his work on video. It’s well worth considering, because some of the work could be jaw dropping.

No less than Bill Malone—one of the finest sleight of hand close-up performers and comedy magicians of his generation, and an enormously successful corporate entertainer—paid tribute to his cherished mentor by producing a six-disk DVD set entitled “Malone Meets Marlo,” in which Malone performs (and explains for magicians), some sixty-five Marlo tricks and card routines. Watching this material will make any Marlo critic think twice, or even thrice, about one’s assessment of his creative range.

Ed Marlo passed away in 1991, and while his name remains a commonplace in conversations and publications about card magic, his contributions have been somewhat diminished by time and absence. While certain technical elements remain ever-present, I fear that contemporary students are far less inclined than those of my generation to commit to penetrating the mysteries of Marlo’s intense and eccentric publications, in favor of the ease of watching another instant download of a forgettable trick, or yet another video “tutorial” on YouTube by an unqualified “instructor.”

Marlo publications consume at least some three feet or more of shelf space in my library, and as I look over them, I recall the pleasures, frustrations, and revelations of the years of study I invested in them. I readily recall reading technical work, early in my studies, that was well over my head and all but incomprehensible. Yet I persevered, and would revisit the material again after a time, capable of understanding a bit more at each attempt. And eventually the day came when it all made clear and simple sense on first reading, and I was surprised that it had ever seemed otherwise. That kind of study and learning and enlightenment gives one a sense of accomplishment, and a measure of one’s advancement and progress—but it’s also just plain fun.

To credit these strengths and values is not to ignore or dismiss the dark side of the Marlo record. But as my Uncle Harold used to say, “Inhabitants of vitreous formation should not practice jactation,” and so I think the remarkable record of Ed Marlo is a subject worth of homage and esteem here, in what comprises my final installment at Magicana of my Take Two series.

images courtesy of the david ben collection

Most of the video that I can provide here is Marlo doing what he did most: demonstrating sleight-of-hand magic and technique for other magicians. You won’t find jokes here; you won’t be wowed by showmanship. Rather you will see some amazing things, if you pay attention—and keep in mind that much, if not most, of it is almost equally amazing for magicians and non-magicians alike.

After another video introduction, here we find Marlo in a “session” at famed Chicago magic landmark, Schulien’s, a multi-generation restaurant and bar that is now gone. This video features a single difficult and highly deceptive poker demonstration with a genuinely shuffled pack.

Here is one of the sixty-five tricks and routines from “Malone Meets Marlo”—an Ed Marlo trick performed by Bill Malone, the noted comedy magician and a truly fine sleight-of-hand expert.

And...

I trust the above samples have provided an interesting taste of the Marlo legend, albeit just a tidbit. For those inclined to watch something more, this is the kind of magic film footage that, before the explosion of home video technology, would circulate as cherished treasure—and currency—in the heyday of magic's underground. This footage, drawn from the video, “It's All In the Cards,” is accompanied by audio commentary from Marlo acolyte, David Solomon (who also produced the video, under the ProPrint name). In Dave’s admiring words: “Look at those chops!”

MORE: TAKE TWO ARCHIVE